Why a billionaire called my MicroConf presentation "cheating"

And why we should all move away from being "data-driven" 👀

MicroConf 2024 was only a couple of weeks ago, but I find myself still reflecting on just a few seconds of a fireside chat between Ben Chestnut — CEO and founder of Mailchimp, sold to Intuit in 2021 for $12B — and Rob Walling — prev. CEO/founder of Drip, currently running TinySeed and MicroConf.

The context is that I had just given my opening keynote about the “Pillars of Product-Led Growth” where I simplified the PLG framework for founders into just three key points:

Get your activation rates up as much as you possibly can; data shows there’s a huge gap here for growth (especially for bootstrapped founders)

Increase your net revenue cohort retentions as high as humanly possible after 12 months (ideally in the 100-120%+ range, but “comfortable” growth is usually 80%+)

Stop guessing when it comes to pricing and monetization because it can easily become the greatest growth lever you have

My goals for this talk were also simple: to remind founders — especially bootstrapped founders — that the levers for product-led growth are actually quite straight-forward and statistically speaking, they’re still leaving a lot of money on the table by not addressing these critical data points.

Part of it has to do with mindset (a lot of founders don’t know how to improve these KPIs, so they leave it alone), but the other part is just lack of knowledge (they simply aren’t thinking about these as their main growth levers because they’ve been fed the marketing-acquisition-kool-aid for too long).

After seeing my talk, Ben said that it was “cheating” and it took him 10 years to figure this out for Mailchimp:1

It was one of the greatest compliments I think I’ve ever received in my entire career.

When a billionaire says your talk is helping everyone cheat, you pay attention. So I, along with hundreds of others in the audience, listened with extreme care to what he had to say about growing Mailchimp.

But what Ben was saying made a lot of sense (all gushing aside, of course).

When Ben was growing Mailchimp, he didn’t have fancy tools to help him understand his PLG SaaS growth. There wasn’t a Stripe or ProfitWell or Amplitude at the time to help him dig deep into what was really going on.

First, he had to conceive of the data he wanted to understand and then build many of these charts from scratch before ever really comprehending what they would reveal.

“PLG” wasn’t really even a concept until about 2016 when OpenView claims to have coined the term.

Other SaaS and software veterans operated under the philosophy of product-led growth without ever having called it PLG:

I think I heard about product-led growth recently, although I've been thinking about it for a long time. I started at Zendesk in 2009, and it was all about product-led growth, but we just didn't call it that. Zendesk was really good at having the first experience of just being able to try the product with ease, sign up for it, try it and buy it without talking to a human. That was definitely part of the strategy. My brain was totally wired from that experience. It's been product-led growth all along.

Amanda Kleha, prev. Chief Customer Officer at Figma, prev. SVP Marketing at Zendesk2

The more veterans in the SaaS and software space I talked to, the more stories I heard of leaders gathering all sorts of data and conducting a myriad of analyses to just simply understand what was going on and where did their best opportunities for growth lie.

Gail Goodman’s talk from Business of Software 2012 about the “Long, Slow, SaaS Ramp of Death” still lives rent-free in my mind, for example.

It’s almost contradictory, in a way, to think of Mailchimp leaders going through such intense analytical processes given how creative and just damn lovable their brand is.

When I think of Mailchimp, I think of brand, design, creativity, and Freddie the monkey. I don’t think of Ben poring over spreadsheets, furiously trying to understand NRR.

But alas — even Mailchimp has to conduct net revenue cohort retention reports, likely by some combination of customer segment, geographic region, and business unit. As they should, just like the rest of us.

Give us all the data! :D

Today, we almost have the opposite problem as Ben did.

There’s a bunch of data. It’s at our fingertips in an instant. Not every piece of data is possible to retrieve (marketing attribution, for example, is getting more and more difficult), but most times, there’s a way to get close enough to the specific answer you’re looking for.

I remember the movement, too, from a marketing perspective when the push to become more “data-driven” became every CEO and marketing leader’s obsession. The CEO could point to a sales dashboard and know every single detail about where the revenue was coming from, but she couldn’t do the same thing to marketing.

Thus began the great investment in marketing attribution.

Product got its wave, too, when it became clear that not everyone could afford the BI tools of the time (nor the internal resources) and SaaS needed its own special breed of product analytics with its own relative price tag.

Then came subscription analytics because some really smart cookies figured out that many CEOs and founders and CROs/CFOs were doing what Ben was doing and crunching it all by hand in a spreadsheet.

As the world became more data-driven, the call came from every corner of the SaaS and software tech spaces: Become more data-driven! It’s all about being data-driven!

At the time, however, “data-driven” had more simple meanings.

“Data-driven decision-making entails using facts, metrics, and data to make strategic business decisions that align with your company’s goals, objectives, and initiatives,” according to Mark Nelson, CEO and President of Tableau.3

But at some point, the order of operations for “being data-driven” got, well, out of order.

While teams did a great job of collecting data, they were also often using it as the starting point for making decisions.

Data, however, shouldn’t necessarily be the starting point for making strategic business decisions. Data should instead inform a decision you’re already trying to make, and that’s likely what Ben was doing when he was calculating NRR by hand.

I don’t actually know, but my guess is he was trying to answer the following questions about Mailchimp:

Who are my most profitable customers?

In general, how are we performing long-term with customers?

Which segments should we focus on?

Which segments should we abandon?

Which segments of customers stay the longest?

Which segments need more improvement?

The first two are simply queries — information to inform.

But the last four questions? Those are all decision-making questions, and my bet is Ben used NRR to inform at least part of their decisions on this for Mailchimp throughout the years.

On being insights-driven

Cambridge Dictionary defines “insight” as the following:

a clear, deep, and sometimes sudden understanding of a complicated problem or situation, or the ability to have such an understanding

Gathering insights requires, to some extent, collecting some form of data, but I think being “insights-driven” is more in service of the purpose — which is to ultimately solve tough problems.

That’s why I like this definition a lot. Data-driven is all about the collecting, storing, and analyzing of data to inform decisions, but insights-driven? We’re solving problems over here.

Growing a business is one big problem to solve, and when you understand its parts within the context of your business, your market, and the revenue model you’re using, then the solutions available to you become more and more clear.

In order to understand, however, you need insights. Too many of us out there are winging it when we should actually be digging our heels in.

My argument is to instead start with understanding what decisions we’re trying to make in our businesses and then gather the insights we need to make them as best as we can.

Quick story: I was chatting with a VP of Marketing at a B2B PLG SaaS about a startup they had just acquired in the last year and they were talking about shutting down the acquired brand versus preserving it.

The acquisition was a huge win for the founders of the startup — double-digit number in the millions and was easily 15x their MRR. The new parent company, however, wasn’t sure if they’d keep the brand name in tact or roll it up under their own brand.

The product, of course, would remain in tact since it would be a lovely addition to their product suite, but the question remained: do we GTM with this product as it is currently named or rebrand to our own branding?

After a few meetings, the VP of Marketing along with others decided to eventually roll it up under their own brand.

I replied, “Interesting! How did you arrive at that conclusion?”

The VP said, “We just decided! Why? Was there something different you’d recommend?”

The acquiring company certainly had a bigger brand presence than the smaller brand, but it was shocking to me that a multimillion-dollar-decision like this one had absolutely zero insights-gathering.

No shade to the VP of course — he busy. But if I were the CEO? I’d have a lot more questions.

When do we need insights, though?

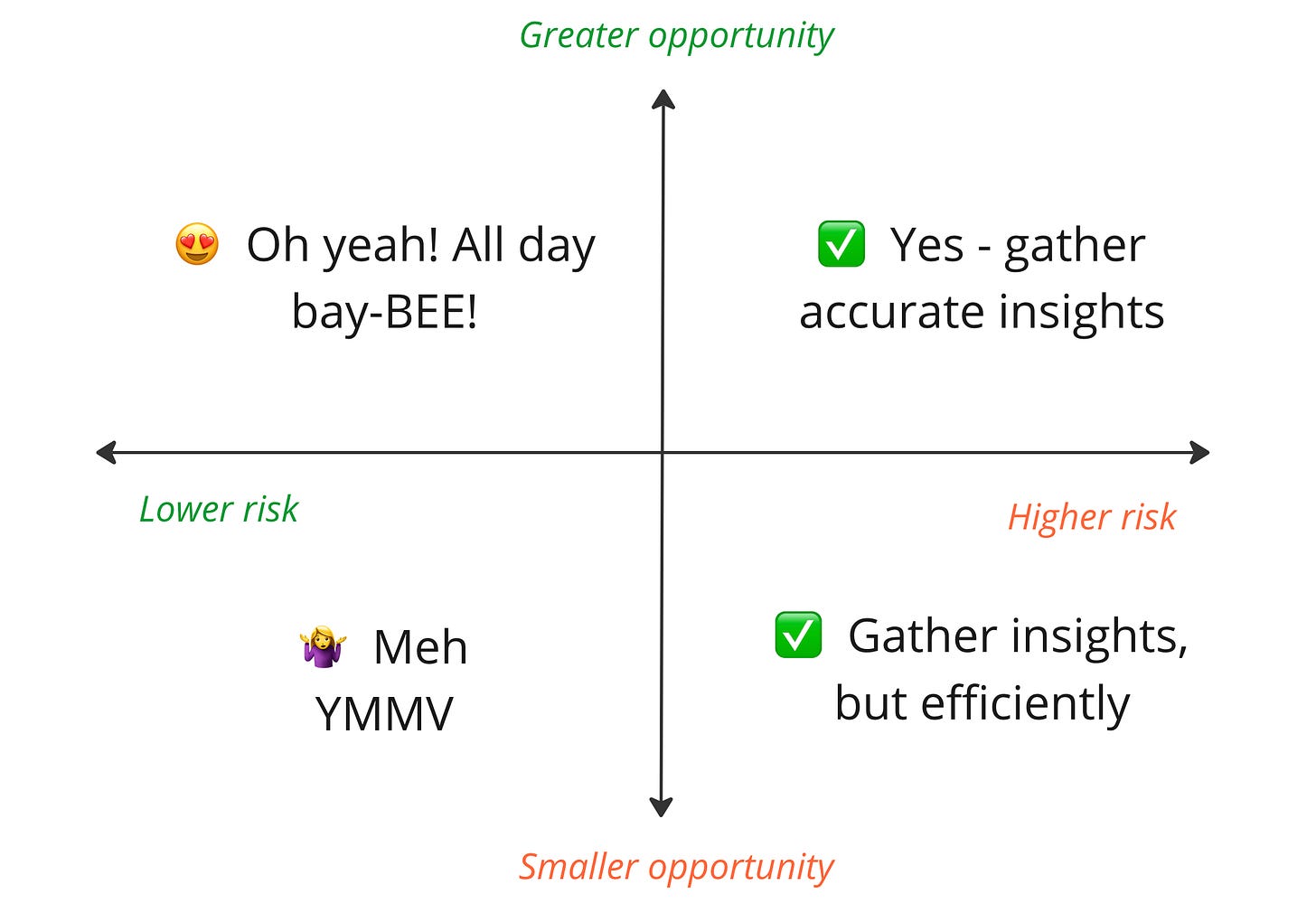

Maybe it goes without saying, but there’s degrees to which we need to be insights-driven. As with most things, there’s nuance.

To keep it simple, I’m using risk as the ultimate deciding factor for if we need more or less insights.

Generally, if we’re making decisions that have small, near negligible consequences, then we don’t probably don’t need that much insights and they probably don’t need to be near perfect information.

Examples: testing paid ads, testing content, updating the sales pitch, making a tweak to a feature, publishing a new marketing page, etc.

If there’s much greater potential for very painful or expensive consequences, then we likely need to gather more insights that we can really trust.

Examples: building the MVP of a product, acquiring a company, testing new pricing, moving upmarket (or downmarket), changing business models, new market expansion, overhauling activation experiences, rebuilding the product, pivoting the product, securing critical partnerships, etc.

There’s another version of this that includes “opportunity” in a matrix — such as if the opportunity has greater upside potential, then there should be more insights-gathering to inform the decision.

Example: while there may be no catastrophic consequence if you make slight tweaks to your main marketing homepage, the potential upside of really SLAYING the copy could triple your MRR if you triple the homepage conversion rate. There are several other examples in the category, but you get the idea.

All of this to say…

I’m calling in the energy of being insights-driven for founders, executive leaders, and their teams.

We can collect all of the data we want (or even none at all) but it won’t do us any good if we aren’t intimately aware of the decisions we’re trying to make first.

So — what decisions are you trying to make right now?

How much opportunity / risk is there for each of those decisions?

What insights do you think you’ll need to make the best possible decision?

Let’s be like Ben, but use the modern tools and data we have access to that he didn’t.

Source from MicroConf.com: link pending

Source from ProductLed.org: https://www.productled.org/blog/interview-when-did-you-first-hear-about-product-led-growth

Source from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tableau/2022/09/23/beyond-the-buzzword-what-does-data-driven-decision-making-really-mean/?sh=7d03374425d6