How to not do product discovery

A real-life example of product discovery in the wild and how we can improve it to get better answers

Note from author: This one’s a little bit longer than 10 minutes 😅 But hopefully worth it! Enjoy!

Before I started working in SaaS, I used to believe that creating new products - whether tangible or digital - was easy.

I used to think that really smart, gifted people with power and money walked around with brilliant ideas all the time and they just created stuff and poof! A winning, profitable product would appear!

I thought God favored these people and he’d strike his favorites with divine inspiration for something magical, beautiful, and money-making.

Little did I know that product development is a practice as much as it is a process, and it all starts with product discovery.

According to Maze.com, “product discovery is the process of researching to understand your users' problems and needs, then validating your solutions before beginning development.”

And just like with most things in business, most people initially are not very good at it.

They have to learn over time — usually by doing, and often the hard way.

The risk of not doing product discovery at all is wasting precious time, money, and resources on building something that people don’t even want but can’t tell you to your face because our genetic coding and societal standards keep us from being overtly confrontational.1

The risk of not doing product discovery well is building something that’s kind-of close to what users want, but isn’t the overwhelmingly positive response that we all crave. The other risk, of course, is being just as bad as not having done it at all.

Believe it or not, some teams and founders do skip product discovery. While the risks here are often obvious (and also absolutely bonkers to me), it’s not-so-obvious when it’s not done well or well-enough to achieve the insights needed to make better product decisions.

<sarcasm>

Because, after all, if you’ve checked the box of “product discovery”, then you should be good, right? Nothing bad will happen because you did as you were told — despite if it was actually impactful or meaningful work, right?

And let not the founder, herself, be bad at product discovery! It’s simply impossible!

</sarcasm>

This brings me to an example of product discovery out there in the wild that had great intentions, but could use some tweaking for maximum insights and impact.

Colin and Samir: YouTubers and aspiring course-creators

This analysis started with a post (née tweet) on X:

I had never heard of Colin and Samir before, but of course, I was curious. All of the replies to this post seemed to imply that people were upset about the course itself rather than not wanting to pay Colin and Samir for their expertise.

So I go to their YouTube channel to try and find the announcement in question and take look at the replies.

Here are the facts from what I’ve been able to gather:

Colin and Samir are YouTubers who create long-form content about entrepreneurship and being a creator

They seem to primarily interview other creators, influencers, and entrepreneurs in the form of a videocast and periodically sprinkle in their own short-form content

They published an announcement on their Community page about launching a course which got mixed feedback — much of it centering around concern and positive reinforcement

This course appears to be mainly about building a business on YouTube

They published the announcement along with a Typeform to collect feedback about this potential course

Several viewers have speculated that the inspiration for a course likely came from an interview with Ali Abdaal, but we don’t know that for sure

Overall, I’m pretty impressed with them. And I’m low-key shocked that YouTube has never floated their content my way considering my absolute die-hard love for YouTubers and the gift of their content.

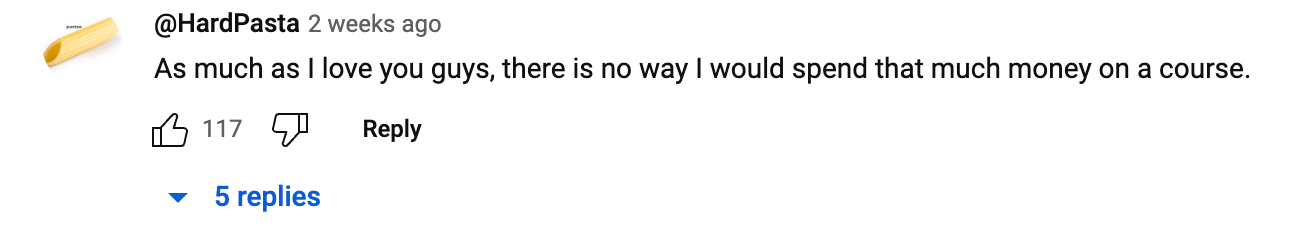

But as for the responses to the course announcement? After reviewing the first 100-150 or so replies, my take is that their audience wasn’t necessarily concerned with Colin and Samir monetizing their expertise, but specifically offering a course that they didn’t necessarily want.

Here’s a few examples of what people said:

From what I gathered from this feedback, it seemed a few more things were true:

People had more concerns about the price — we’ll see later in the teardown that the form was actually misleading in terms of pricing and can easily lead to false positives since the minimum price was set very high in their opinion

There were also concerns about the subject matter — a course about “brand deals” for example wasn’t exactly what people had in mind when they thought about Colin and Samir

Finally, there’s concerns about the medium itself of a “course” — courses on YouTube have a bad reputation because of the thousands of people out there producing and selling low-quality, low-impact courses while charging top-dollar for them. We saw this most prevalent in the fitness space with fitness influencers and “entrepreneurs” selling courses about how to sell a course

So, actually, there wasn’t much feedback about Colin and Samir monetizing their expertise. Like no one was mad that Colin and Samir would charge for something or sell something to their audience.

It seems most of the responses are in genuine support of Colin and Samir; it’s just that they were caught off-guard, and it had everything to do with the above reasons.

Half-baked product discovery

This brings me to the feedback form itself (which of course I could not resist and I had to click it to see how they were gathering feedback from their audience).

And this is where I was reminded that even though we may have the best intentions for gathering data, we still may accidentally sabotage ourselves by how we approach it.

This is why product discovery is so damn hard and why it takes a lot to overcome this skills gap.

A few disclaimers before I dive into the form:

My goal here is not at all to personally critique Colin and Samir. I’m sure they’re incredibly nice, well-intentioned guys who are not at all scammy or have questionable behavior… at least, that’s the impression I get.

I’m also not here to rip apart this form. My mission is to show you how to re-write and re-structure this form to obtain maximum value, insights, and ultimately impact based on the goals you might have.

I don’t want to imply that Colin and Samir’s idea will fall apart just because this one form wasn’t optimized. It’s actually very likely that a large enough segment of people will love a course about brand deals and would have paid even more than what the options were. It might be worth it for C & S to build the course anyways and sell it (but my strong guess is that it’s not the majority at all).

Okay let’s dig in!

So we have the first question that asks what brings us to the survey. Great question!

Here’s the problem with the answers: they’re combining two sets of information into too few options:

My status as a creator

My intention or goal

The issue with doing this is that it’s leading the respondent into answering in a particular way and not taking into consideration the infinite options out there in the world that could be true. Such as:

Being a full-time creator but not at all interested in closing brand deals

Being a newer creator and already having it figured out how to monetize content but actually struggling with something else

Being on a creator’s team and already knowing how to support growth

That leaves a lot of people selecting options that don’t actually align with the truth or reality of the situation. In research, we call these “leading answers”.

Recommendation: Split this into two separate questions. Ask first about which best describes me as a creator: full-time creator, newer creator, part of a creator’s team, and an aspiring creator who maybe isn’t there yet.

Then ask what my goal is for my creator brand. We technically already have a question related to what I’d like to learn from Colin and Samir specifically, but it would be helpful to know generally what my goals are with my creator brand so Colin and Samir and brainstorm/prioritize accordingly.

This data would, in theory, give us an understanding of how committed or serious someone is about their business and may have an implication on how much they might pay for a course.

This one’s pretty benign. No issues here, but I do think it’s interesting that they immediately jump to asking us about brand deals.

Recommendation: We need to qualify the need for brand deals first. If we wanted to be more true to the product discovery process, we’d first ask “Have you ever considered adding brand deals to your revenue model?” and then maybe “Are there any challenges that you have with getting brand deals?”

That way we can identify the need first and then understand what problems there may be with brand deals.

If you find that the vast majority of respondents aren’t actually thinking about brand deals, don’t desire them, and aren’t excited about figuring out how to get them, then you know you can save your time building that course for that audience.

This question is also benign — especially with the “Other” category for me to fill in other answers. But my guess is they aren’t thinking about the other various ways that creators can create (such as Twitter/X, Facebook, Patreon, etc.) or maybe just don’t care.

Not going to nitpick this one. I’d leave it as-is, but this list probably could be expanded a bit.

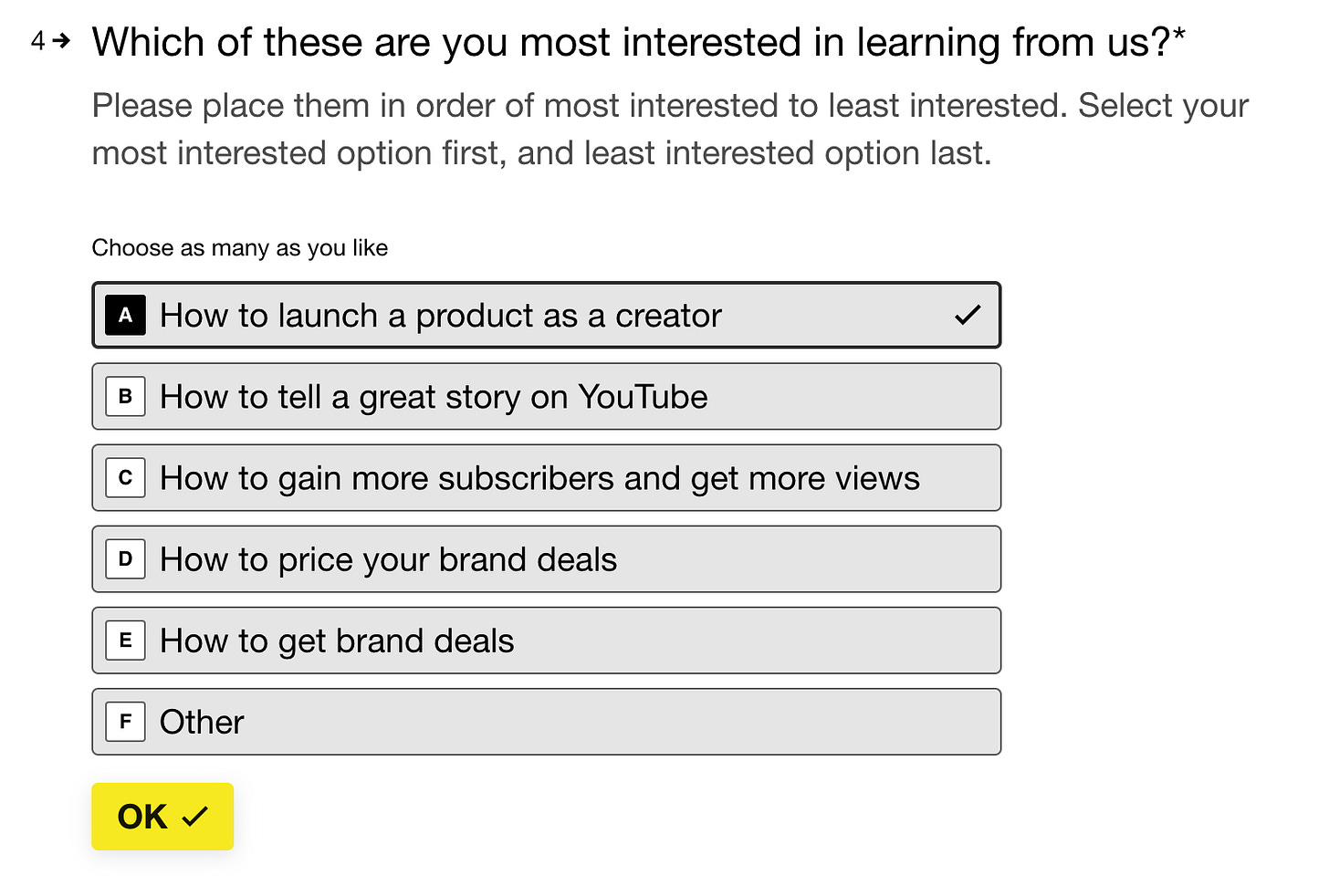

I’m actually not mad at all about this question as much as I am the experience of it. It says to “Choose as many as you like” but it also says to “Place them in order of most interested to least interested” without the ability to actually select an order.

I think maybe this question just wasn’t configured properly, but I do genuinely like the options.

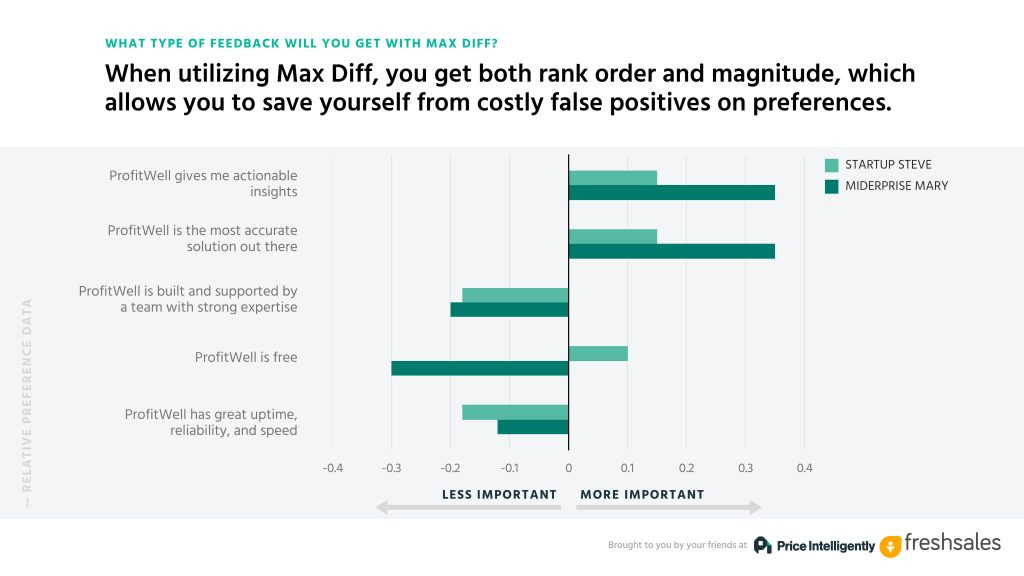

Recommendation: What would be even more powerful would be to ask a relative preference question where you prompt people to select one option that is most interesting and select one that is least interesting to them. When you compare the results, you’ll end up with a chart like this:

This will help Colin and Samir prioritize the topics and themes according to whom they consider to be a high-value audience member.

It’s even more impactful when we segment the data and analyze it according to their price sensitivity or other variables like experience-level like in that chart above, but this is definitely more advanced.

And finally, the real kicker. So by the time we get to this question, a few assumptions have happened — it’s assumed that I care about brand deals, that I want a course about it, and that $500 is the absolute minimum I’d pay.

Technically none of these are true, and I imagine that many people completed this survey and gave leading information because it wasn’t structured well. Either that, or they got to this point and just gave up like this lady:

Recommendation: Adjust the answers of this question. If there was nothing else I could change about this survey, I’d at least change this question to do a couple of things:

Include an option to indicate that I’m not interested in a course about brand deals

Include smaller ranges — such as $150 - 300 and $301 to 499. There’s a lot of nuance when it comes to pricing in general and especially to consumers

My guess is that many people will complete this survey selecting the first option when in reality, they’d pay much less. This will be misleading for Colin and Samir and may lead them to believe that charging $500-1000 will be a no-brainer price for their audience.

If you’re thinking to yourself, “But wouldn’t people see that and just bail? And then I’d only get information from people who actually would pay at least that much?”

This might be true, but even in that case, wouldn’t you want to know how much of your audience would be priced out or would pay much less?

Let’s say your audience is 100 people and 90% of them would only pay $150, but 5% of them would pay $1,000 for the course. You can either make $13,500 or $5,000 based on those stats.

That’s why we need to represent a fuller range of prices (even if we wouldn’t want to actually charge that).

The missing discovery questions

Generally speaking, this form is an okay-start. I’m glad they’re at least doing it to collect some information, but I fear that much of it will be misleading due to some of the inherent bias present within the survey.

I know the conventional wisdom out there is to keep surveys short (and generally I agree), but for this one, we can afford to add a few more questions to improve the quality of the insights. This in turn will help us make even better decisions.

Here’s what I’d add:

Ask about learning preferences

“Which of these methods do you prefer to learn from?” (options: courses, podcasts, webinars, workshops, books, audio books, etc.) —> this tells you if a course is even the right medium for that highest-value audience members you have

Bonus: we can make this a relative preference question as well and phrase it like “Which of these learning methods do you consider to be the most impactful versus least impactful” and let the responses be your guide

Ask about previous course experiences

“Have you ever purchased a course from a creator or YouTuber before?” —> this tells you how much experience someone already had with a course

Ask about desired outcomes of the course

“What would you hope this course would help you accomplish if you took it?” —> this gives you clear expectations for what your course might need to contain in order to be impactful

“How do you imagine life would be better after taking the course?” —> helps you paint the future reality and understand expectations they may have about the course

Ask about dealbreakers

“What would make you not buy the course?” —> this helps you get ahead of any anxieties the audience may have about the course

Ask price sensitivity questions

These include the famous Van Westendorp questions related to price sensitivity:

At what price would you consider the product to be so expensive that you would not consider buying it? (Too expensive)

At what price would you consider the product to be priced so low that you would feel the quality couldn’t be very good? (Too cheap)

At what price would you consider the product starting to get expensive, so that it is not out of the question, but you would have to give some thought to buying it? (Expensive/High Side)

At what price would you consider the product to be a bargain—a great buy for the money? (Cheap/Good Value)

Once analyzed, you end up with a chart like this:

Ask to participate in an interview :)

“Would you be open to participating in an interview about your experience and challenges as a creator?” —> plant the seed for future interviews to dig even deeper; surveys tend to be too high-level and usually don’t have enough context

By adding these questions, we can expand our understanding of the audience while also challenging our own assumptions about the ideas we have. Running an updated survey would undoubtedly uncover more accurate information.

When combined with interviews, they would achieve the maximum effect of building something that the majority of people want and would pay for rather than assuming a course about brand deals is the way to go.

Improving your own product discovery skills

Getting good at product discovery depends on two skills:

Natural curiosity: You really want to understand you audience and/or customers and are genuinely curious about how and what people think

Low ego: You are not attached to your ideas and are willing and ready to be humbled

Founders and product leaders who struggle with product discovery tend to come at it from a place of confirmation bias — they already have an idea of what they want to build and while they will “conduct research”, it only confirms what they already believe based on how they approach the research.

Since confirmation bias is based on what you already believe, we need only ask a few questions to identify it and unpack it:

What do I believe to be true about:

What my customers value or care about?

How they use the product?

What they do after using the product?

The value my customers receive from using the product?

Why customers want certain features?

What requirements customers have about the product/feature?

Where do these beliefs come from?

Is it from real voice of customer or from watching their behaviors?

Is it based on any data from any platforms?

Is it based on what I think I know or do I actually know from these sources of data?

What do I want to build or provide my customers that hasn’t been validated yet with qualitative or quantitative insights?

What ideas am I currently attached to?

When I gathered qualitative insights, did I assume the customer cared or desired what I was asking about?

How and where did I make those assumptions?

Were any of my questions assumptive?

Were any of my answers assumptive?

Asking yourself these questions and having a little deep-think will uncover a few areas where you may have been accidentally biasing yourself in your product discovery process.

It’s not your fault though — we all do it. Even me, sometimes! Product discovery is hard after all, but hopefully after this, we can all get a little bit better.

And if you know Colin and Samir, tell them I’d love to help on their next product discovery project. :) ✨

This, of course, is the premise of the beloved book “The Mom Test” by Rob Fitzpatrick which I highly recommend everyone read.