Why "raising your prices" isn't the actual strategy

It's only part of the story; the rest of the story is the work

You’ve heard the wisdom before from all kinds of SaaS leaders, influencers, and makers:

“Raise your prices!”

“You’re not charging enough!”

“The pricing on these plans are rookie numbers! Get those numbers up!”

Most founders and teams hear “raise your prices” and then immediately do it without conducting much research or gathering much data about the levers they can pull within their current pricing model.

And don’t get me wrong — this isn’t bad advice, but it is incomplete advice.

Don’t believe me? Allow me to remind you of Baremetrics’ price increase1, immediate lift in revenue, and then the slow trickle into the same growth trajectory that they were on before.

Now to be fair, part of this was due to the wildly unpopular “Call to Cancel” strategy that was deployed, but also due to poor communications around this pricing change.

Even still, simply saying “raise your prices!” is only a small part of the work.

In the growth work I do with founders and their growth teams, pricing and monetization inevitably ends up on the table as an opportunity.

Sometimes, the founder already ratcheted up their pricing plans only to discover 6 months or so later that they suddenly had a big churn problem or low net revenue cohort retention.

When we dig deeper and ask, “What was your pricing strategy that led you to these conclusions?”, it’s usually a shrug and a “I heard someone from so-and-so conference that I just should.”2

It’s common wisdom that most B2B SaaS companies3 are likely undercharging (especially those of bootstrapped founders), but sometimes just taking your existing pricing and plans and notching it up by some percentage doesn’t actually create sustainable, meaningful growth over the long-term.

This is especially true if you don’t have a customer base to support this change in pricing and/or if you’re not already attracting a portion of the market that can pay the new price.

I’ve seen this before. What will happen is it then triggers an internal existential crisis that marketing needs to ramp up a bunch of top-of-the-funnel growth because the change in the model didn’t actually match the overall GTM strategy in the first place.

And what’s even worse is if your new pricing can’t actually be justified by the market segments you’re currently targeting, then it creates more churn and really slow growth moving forward.

So, sure, increase prices — but maybe let’s gather some data first to give us context about:

How much we can raise prices

If we can increase prices by adjusting the features in the existing plans today

Turn certain features into add-ons (thereby creating expansion revenue opportunities)

If the existing customer base that you already have can support a higher pricing tier and who they are

What potential pricing experiments we can run to give us insights into where to go next.

And if you’re thinking, “Woo! This sounds like a lot of work, Asia!” and you’re already exhausted, then you would be right. It is a lot of work, but friendly reminder that monetization is one of the activities that gives us the best bang for our growth buck and you don’t have to do it alone.

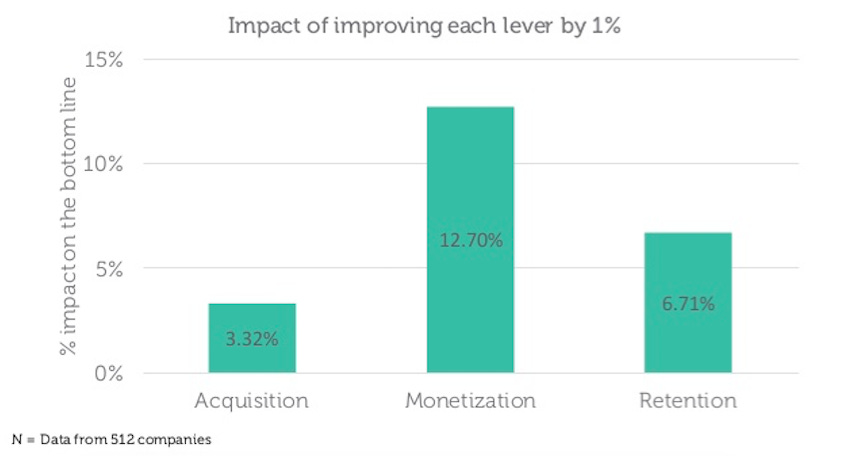

A small change in pricing or monetization can give us 3-4x more return than a small change in acquisition.

Plus — why would we guess when we can know? Or at least illuminate the path more than just picking another arbitrary number on top of the already arbitrary number you picked before?

Tools to inform your pricing strategy (because guessing is so early 2000s)

So what do we do? There’s a few tools we use, all inspired by the Price Intelligently team along with our own experience:

Price sensitivity survey using the Van Westendorp pricing model4

We combine this with the all-famous Product-Market Survey popularized by Basecamp and Superhuman and a Value Preference Analysis (or Feature Preference Analysis) that asks about the most and least important features

We then filter this data by the amount of people who say “Very Disappointed” to the affinity question + general qualification data to get to the ideal paying customer versus less-ideal customers

We end up with a series of charts that display price sensitivity across various cohorts that tells us a lot about what people value and which people value different things more than others

Price elasticity based on the same qualitative data points from above

This is calculated using the charts from the price sensitivity graph, but will show you what percentage of deals/customers you’ll lose at certain price points

Website surveys that run exclusively on the pricing page

Limit questions to understanding who the visitor is (aka if they’re qualified) and if pricing matches their expectations

Also a great opportunity to gather UX insights about the page (a la if anything is confusing or unclear)

Customer interviews

Both of brand-new customers (like the last 2-3 months) and of existing customers with the focus of getting feedback on the existing pricing

If you do nothing else, do this and the price sensitivity survey

Audience interviews from ideal, qualified prospects who may be complete strangers

Feedback here gives you first impressions and insights around the trade-offs or comparisons the audience would make

The insights from this audience, however, need to be taken with a grain of salt since audience members are not actual paying customers and haven’t made any real trade-offs in the buying process

The best part? You don’t need gobs and gobs of interviews for this. Just 3-4 pricing-focused interviews will be enough to gather meaningful insights to make better decisions. When running a price sensitivity survey, shoot for ~50 responses from a variety of customers to inform potential options for plans.

Collecting the insights you need to make progress on monetization is closer to you than you think.

Here are a few things to keep in mind, though, when gathering this data:

What this data won’t do

First and foremost, it’s not going to tell you exactly what your pricing should be. What it will tell you is how your customers think about pricing, and how your ideal prospects think about making trade-offs based on your pricing in comparison to alternatives.

We collect all of these insights to arrive at a pricing strategy that mutually benefits the consumer and the business, but just running a survey doesn’t mean we just brush our hands, take the price that people seem to want to pay, and then move on.

We’ve gotta develop a few experiments and put them to the test! This process is iterative and builds upon itself.

Second, we don’t do this work once and leave it alone forever. We do this work to inform our first pricing experiments, and then we continue to iterate as our platform and customer base grows.

Too many founders and early-stage teams assume that once the pricing is set, it’s set forever and no changes are made after the fact.5 It’s as if the entire growth lever disappears in their mind forever until a chief revenue officer comes along and says, “Hey, why haven’t we increased prices or changed the plans in the last 5 years?”

Remember: as the market changes, so should your GTM strategy (which ding ding ding! includes your pricing strategy).

What this data will do

Gathering this information will enable a few things:

Inform decisions related to existing plans and their dollar values: Instead of operating with 10% insights, you’ll operate with 70% insights. You do have some data available to you, and that’s what customers are paying now and what types of customers pay more. Opening up the hood and conducting your own analysis is guaranteed to illuminate a few things. Technically everything is always a “guess” but at least the guessing will be infinitely more informed (and more likely to succeed).

Create the foundation for future pricing experiments: With data and qualitative insights come opportunities to test new ideas and see which combination of efforts creates a win-win for the business and the customer. Saying it simpler — if you get over this hump, everything after builds upon the knowledge you gained in the first round which means it gets even easier over time to test pricing.

Highlight UX issues with the existing pricing page: Because nothing humbles you faster than seeing someone navigate your pricing page, get really confused, and give up because they don’t understand anything about what they’re getting for the money they see on the page.

Pricing experimentation in the wild

You’ve undoubtedly seen pricing experiments in the wild — likely without even realizing it.

Most of us in the SaaS space are keenly aware when a product we’re using changes their pricing (I’m thinking of you, Intercom), but I’d wager most of us are not super dialed-in to pricing tests our favorite SaaS co’s make.

The examples most blogs love to cover are Shopify and Zendesk, and you can see the iterations in pricing over time — likely designed by some combination of intuition and a bunch of qualitative research and number-crunching on the revenue and retention side.

Zendesk had several iterations of pricing over the years, but it’s still amusing to see how they went from this in 2008:

To this in 2011:

To this in 2016:

To this in 2023:

There’s even more than what I’ve covered here, but the full article is fascinating.

Take your favorite SaaS company, throw their pricing page into Wayback Machine, and see if they’ve run pricing tests over the years. You may be surprised at which companies are actively turning the monetization dial and which ones are decidedly not.

Hopefully after today’s edition, I’ve convinced you that you absolutely should be turning the monetization dial (but to back it with insights first!). 😉

Arvid Kahl interviews Brian Sierakowski (prev. CEO of Baremetrics) in an episode of The Bootstrapped Founder and Brian briefly discusses the price increase, the poor communication around the pricing change, and subsequent churn that happened afterwards.

No tea, no shade to speakers who make this recommendation — especially if they’re encouraging actually doing the work to really figure out what your monetization options are and testing the various approaches to see what works. Patrick Campbell, for example, absolutely recommends increasing prices where it makes sense, but to also do the work to figure it out.

B2C / consumer SaaS is a slightly different story since they’re more susceptible to market changes. Take with a giant grain of salt if you’re at a B2C or consumer SaaS and you hear the feedback to increase prices.

If you’ve ever wondered how these fancy charts get made, this is how! Highly recommend saving this page if you ever plan on running it yourself.

It makes sense why — who wants to do all of this work just to turn around and do it again and again?