Reflections on my client's 12x growth

A few observations helping a client's MRR go brrr from 2020 to today.

As the year comes to a close, I can’t help but reflect on one of the clients we’ve been working with the longest — three years to be exact. It will be four years next March.

Usually the tides of market changes and general business stuff catches me and I don’t have much time to reflect on things, but when I do, the gears start turning.

Why was this particular client so successful in growing their MRR? What about them or their context or their actions supported their success?

I can’t speak from all facets since I don’t have all of the information, but I can at least share my perspective from the outside looking in.

Here’s what I’ve learned from working with this client, a B2B SaaS company with a distributed team with 12x MRR growth (and counting).

Context about DemandMaven’s role

It all started when the founder reached out for help regarding marketing his product and feeling like he had a handle on “all the things” from a marketing perspective.

This was back in early 2020 in the before-times when we were bright-eyed and bushy-tailed regarding how we’d approach the project.

We started how a lot of our projects start, and that was qualitative research and a bit of an analysis in terms of marketing performance.

After the initial project, DemandMaven stepped in mostly from an ongoing advisory and consulting role with marketing project management support. We were responsible for tracking performance, running weekly marketing meetings, project management of our various marketing projects, and ongoing consulting and guidance for the team to execute.

We’ve created hundreds of artifacts and deliverables over the years, and have worked long enough with them that I’ve had the pleasure of updating my own work from several years ago many times over.

On the client-side, we had the founder (who wore many hats) and a part-time paid acquisition specialist. There were a few designers and writers that we worked with, but all were freelance.

Over the years, the team wouldn’t add another marketer until 2023 when we hired our first product marketer.

Assuming all other factors are solid, it really is about distribution

You’ve already heard it, but I’m here to say it again for those in the back: it really does just take a few channels that have a strong enough CAC/CPL and relatively healthy buyback period to make your SaaS explode.

But — all other factors also have to be true:

Monetization needs to support growth by naturally creating as much expansion revenue as possible

The product actually does need to be quite solid and serve an underserved market in a way the other products don’t

The market needs to actually believe your product is hot sh*t and genuinely value the progress it helps them make

If those are true, you too can make the money machine go brrrr. And yes, they have to absolutely positively be true.

If they are not true, then the growth may not be as powerful or cost-effective — even if the acquisition channels are cheap and easy to gain traction in. If the bottom of the funnel is leaky or there’s not a strong enough foundation, then it’s a canopy fire at the top.

What made my client’s growth work was a fundamental understanding of how their own business grows and how customers demand value and generate future opportunities for needs to be met.

If we didn’t have that foundational understanding of our growth loops and the levers that made money, all of the acquisition in the world wouldn’t have mattered.

I can hear founders and marketers asking, “Okay, we get it, but what were the channels?”

Sure. Keep in mind, though, that the channels don’t matter as much as your ability to execute against them well enough to see results.

I know that’s a tough concept to grasp if you’ve never felt the feeling of a channel gaining momentum and producing desired results, but I promise you the “which channel” question isn’t nearly as important as answering the “why this specific channel”, “why this channel now”, and “how much can I afford to spend” questions.

Our early channel strategy

Early channels included Capterra, Google Ads, Facebook Ads, and Facebook communities. Most of the growth came from these early channels, and some of the best customers came from word of mouth and referrals that were happening in Facebook groups. I think our spend was around $5k-7k per month at this time, and most of it went to Google Ads.

Organic efforts were simple — when the founder had interesting things to share, he’d publish to their customer community on Facebook.

Customers and prospects would tag the founder in other communities on Facebook and he would jump in and answer questions. He’d also suggest the product as something to try if people were vocally frustrated with some of the competitors.

Eventually, this happened naturally and word of mouth was generated on its own.

Over time, we invested in channels like SEO, and tested other review sites like TrustPilot and G2. We had a few hiccups with SEO and some of the partners we used, but eventually we found a provider who was more attentive.

Other organic channels included partnerships — primarily with other products in the ecosystem that we could integrate with and create more value for customers. We also tested things like PR, affiliates, and various types of conferences.

I’d say the ultimate and-all-be-all channel for our growth, however, was word of mouth. WOM is the hardest channel to invest in because it doesn’t have a directly attributable source or impact, but the founder knew if he could nail it, it would be the ultimate acquisition engine.

The founder probably wasn’t thinking about it like this in the same way that I was thinking about it at the time, but he generated word of mouth by creating something worth discussing, and encouraging others to talk about it in the channels they were already in (á la Facebook).

Our marketing programs were relatively simple:

We had a Facebook community of our customers that we posted regularly in

There’s a weekly webinar that covers the product for prospects who are on the fence about starting a trial but don’t want to speak to a representative

Demand generation programs were very early also, and we didn’t start much true demand generation work until 2023/2022 with an industry report and a few guides

Come to think of it, however, the founder did create a few guides related to OTAs that helped generate early customers, but they were assets that were never updated and invested in as the years went on

We also did have a more robust website that could be counted as early demand gen, but I digress

Onboarding emails (but to be honest, I would say we still haven’t quite nailed this, but we’re working on it!)

Partnership and integration announcements

Product announcements

There wasn’t much lead generation apart from focusing on promoting the free trial, and we’re just planting the seeds for implementing an actual demand generation function in the org, but it’s all a WIP!

How did we figure this part out?

Lord — I hate to say it was intuitive, but it just was.

Google Ads, Capterra, and Facebook Groups were what the founder tried first and found his first results with. He hired a paid acquisition specialist who had tons of experience running ads for other SaaS and software companies with big and small budgets.

That specialist figured out exactly what knobs to turn to make the channel profitable, but it took a lot of time and troubleshooting.1 Eventually that specialist became our part-time paid acquisition manager.

Everything else we layered on as a test, but generally, we followed the energy and minded the budget. Simplest wisdom ever for layering on channels.

On layering new channels:

Follow the energy, and mind the budget.

If we detected a pulse with a new channel, we tried it again to see if it would net the same or better result.

If we saw an improvement, then we likely needed to figure out how to execute the channel in a way that generated even more positive results. This was usually a good sign, but also meant that we’d need to better understand the effort required to achieve desired results.2

Some investments didn’t always seem to have a positive effect (like PR) and there will always be practices and experiments that we’ll never truly know the impact of, but there were others that clearly were not effective channels for us (like affiliates).

Maybe they could work, but given other lower-effort, higher-impact channels, we never circled back around to them (although never say never!).3

If we had never found viable channels, we wouldn’t have achieved the same growth.

We also would have spent way more energy troubleshooting the channels, figuring out where our audience hangs out, and also taking a deeper look at product.

Founder’s mojo doesn’t scale

In the book The Small Business Lifecycle, Charlie Gilkey describes “founder’s mojo” as:

What powers the creation and growth of early-stage businesses (but also what keeps them stuck from growing beyond). It’s the amalgam of intuition, vision, experience, and drivenness that enables a founder to be more effective, decisive, and risk-tolerant than the rest of her team.

But there are only so many things the generator can power at once. As a business grows, there are more things needing juice than the generator can power simultaneously.

If you’re a founder, you’ve got founder’s mojo.

Founder’s mojo, however, can only get a company so far before other people need to be enabled to take the reigns.

In my client’s case, the company was initially fueled by founder’s mojo. They all infused energy in parts of the business that most needed it. In total, there were three founders, and they all contributed energy to get the business going.4

As they grew, it got to a point where if the CEO didn’t hire the right people and get things off his plate, they’d burn out (and it wouldn’t be pretty).

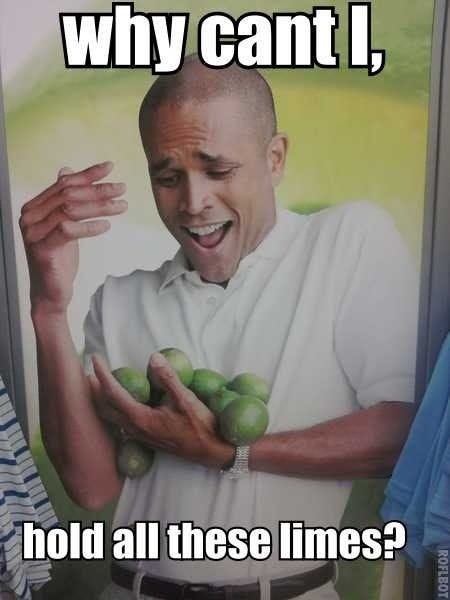

I distinctly remember a point along the journey where it was clear the CEO “couldn’t hold all of the limes” anymore in the business. He was getting pulled in a million different directions and just simply couldn’t do it all.

As a business owner myself, I’ve been there!

I remember telling him that I thought he needed someone who was more operational than he was to make the business run more effectively (and to alleviate a lot of the task-creep and pressure on his plate). It also seemed like he needed help specifically with hiring.

A few months later, he hired a Head of Operations. Once we hired the Head of Operations, a considerable change happened in the business.

Hiring got easier (and faster). Data operations improved. Our tech stack got a much needed upgrade. Teams were finally collaborating together and we had visibility across the whole organization for the first time ever.

I’m not saying hiring a head of operations is something you should do, but I am saying that we were running purely on founder’s mojo at first. Once we got the right folks in place, we weren’t as dependent on founder’s mojo in the same way as before.

I also don’t believe we would have grown as quickly as we did if we had only relied on founder’s mojo alone (at least, not without pretty big consequences such as burnout).

Strategic bets matter

It doesn’t matter what kind of business you run — you’ve got to make strategic bets.

According to HBR, “Strategy means making the best possible choices you can make today and then being responsive when the bets do or do not come in as hoped.”

If you’re in any kind of business, you are constantly making strategic bets about your future state — even if you aren’t totally aware of them. You make your bets now based on some future vision you have for the business.

Those bets come with tradeoffs for the present, however, and if we’re not committed to the bets, then we never get to reap the rewards later.

Making bets and actually committing to them is hard, though. Most people aren’t patient, focused, or disciplined enough. It’s too easy to get distracted, to forget, or let feelings get in the way.

And if you fear failure or the pain of making a wrong bet, then it further fuels your mindset around taking risks in the first place.

The strategic bets you make will determine how your business survives and thrives in any given environment. My client made several that I think ultimately paid off:

Not taking traditional VC funding (like so many of the competitors had)

They had seen what happened when competitors in this industry took on too much funding and succumbed to the pressures of becoming the unicorn in a VC’s portfolio.

The founders opted for a combination of bootstrapping and indie funding instead, and I think this served their vibe far more than the traditional VC route.

Doubling-down on “quality” in a sea of lower-quality experiences

The product had an incredible UX and product design in a world where the competitors had buggy experiences or UI that wasn’t as visually pleasing.

Good design and UX was already a core value to the founders — they didn’t want to build something that didn’t inspire their audience. It wasn’t wild and crazy gorgeous Silicon Valley UX, either. It just looked and felt better than the other products on the market (which wasn’t that hard to do).

Because of that strategic bet, we were seen as the “quality” brand in the market; other brands were seen as more cost-effective or more “first-time founder-friendly”, but overall brand perception was that we were exceptionally good at what we did and it was going to work every single time.

Over time, “quality” and “reliability” became less of a factor as competitors caught up, but it’s still the perception people have of the brand to this day.

GTM strategy that perfectly aligned with the target audience

We had pricing and monetization that was competitive and more palatable to the market (most of the competitors were taking percentages of revenue or had high onboarding fees in place of monthly plans or usage-based pricing).

The product was centered around quality, but also had features that were thoughtfully-designed. Most people can’t describe specifically why or how the UX is better, but they could feel it every time they used it.

They focused on a part of the market that was serious about the growth of their own business, and built features accordingly. This naturally fueled the growth engine of my client’s business as customers grew and so did their monthly subscription price, but because of the solid monetization strategy, it wasn’t painful to them.

Finally, they figured out how to reach this market as affordably as possible - even if the early channels weren’t actually scalable. With all other things in place, they had a way to access customers in channels they already were using.

Clear understanding and alignment of the ICP

The ideal paying customer was, for the most part, crystal clear in the eyes of sales, product, and marketing. While there might be different segments we’re focused on at any given time, I don’t think there was ever confusion about who the ideal buyers were.

If they didn’t qualify, sales didn’t work to close them anyway. They’d only churn later. This was a tradeoff of having focus, but in the end, I think it paid off.

When opportunities emerged to target a different segment within the market that appeared to be more lucrative long-term, we adjusted the ICP. I’d argue though that we never really “shifted”; only that we got “more focused.”

It was clear what the differences were between a great paying customer and a customer who might not have been the best-fit; we couldn’t have done this though without part founder-intuition and part analysis/research/quantitative insights. EOD, the customers who paid more and grew with us over time were people who fundamentally were committed to growing their business and cared about doing it “right.”

There are more strategic bets that we’ve made and will continue to make as we grow and progress, but it’s still so interesting to think about all of the things that fundamentally went “right.”

What are the bets that you’re making either for or in your business?

Yes — the tactics themselves and our ability to execute them certainly paid off for my client in the end, but these tactics were derived from the bets they made.

And it makes me wonder — what about your bets? What about our bets?

What are we (the royal we) betting the farm on? And do those bets make sense given the market context(s) that we’re in?

The trickiest part about making a bet is not knowing if it will yield. But we do it anyway, and ideally we’re making choices that greater our odds.

If I had to simplify it, my client grew because of four things:

Channels

Team / Hiring

Strategic bets

Winning GTM strategy

If you had to simplify yours down to the top 3-5 things, what would they be?

And if you were to fast-forward to 10 years from now when you’re whatever-gazillion-in-MRR, what do you think they would have been?

Now that is the question to ponder.

Troubleshooting here means testing various value propositions, landing page copy, and funnels. It also meant investing quite a bit into the marketing site to ensure it performed.

I’ll add that while this is not a perfect science, sometimes it pays to approach it more intuitively. Many people forget that there is a level of technical prowess required for most channels, so expertise and experience are highly valued and regarded. Long gone are the days where you can just show up on a channel and it just magically works with minimal effort.

Note that I didn’t say “low effort” channels, but “lower effort” channels. Big difference! It just means we prioritized what was relatively easier for us to execute than other channels.

For context, there were three co-founders, also all distributed, and none of them were initially full-time on the product. Two were technical and one we can consider more sales/marketing. I think this also supported later business growth.